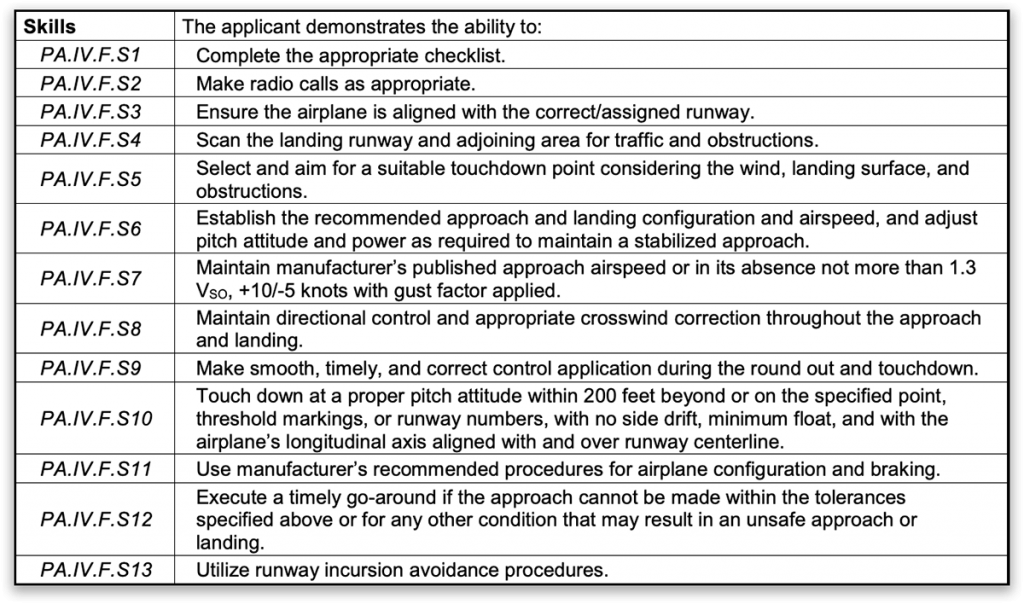

IV. Takeoffs, Landings, and Go-Arounds, Task F. Short-Field Approach and Landing (ASEL, AMEL)

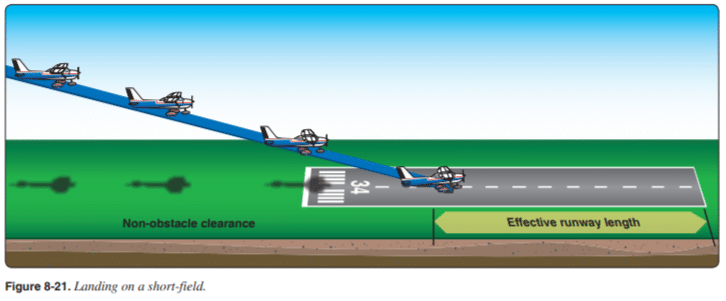

The Short-Field Approach and Landing task features 13 skill elements. Most of these are straightforward but notice that the applicant is evaluated not only on whether they “touch down at a proper pitch attitude within 200 feet beyond or on the specified point” (PA.IV.F.S10) but also that, if necessary, they “execute a timely go-around” (PA.IV.F.S13).

Let’s understand from an evaluation standpoint how unsatisfactory performance is determined, not just for the Short-Field Approach and Landing, but for all tasks. Again, we don’t have to look far — it’s in the ACS. Specifically, in Appendix 5: Practical Test Roles, Responsibilities, and Outcomes. (click to expand)

Unsatisfactory Performance

Typical areas of unsatisfactory performance and grounds for disqualification include:

• Any action or lack of action by the applicant that requires corrective intervention by the evaluator to maintain safe flight.

• Failure to use proper and effective visual scanning techniques to clear the area before and while performing maneuvers.

• Consistently exceeding tolerances stated in the skill elements of the Task.

• Failure to take prompt corrective action when tolerances are exceeded.

• Failure to exercise risk management.

If, in the judgment of the evaluator, the applicant does not meet the standards for any Task, the applicant fails the Task and associated Area of Operation.

The highlighted language above (bold highlights added by me, not the FAA) represents some of the discretion granted to evaluators in terms of accepting performance which is outside of tolerances. This goes hand in hand with “failure to take prompt corrective action when tolerances are exceeded,” another reason for Unsatisfactory Performance. This is why evaluators typically brief their applicants that if they find themselves exceeding a tolerance during a flight portion task, to make it a point to get back within them quickly!

But in the case of the Short-Field Approach and Landing task, it is difficult for evaluators to accept a landing out of tolerance given that the decision to go around is also being evaluated. There’s a Risk Management element referencing the go-around, as well: “Planning for: Go-Around and rejected landing” (PA.IV.F.R3a).

Get the message? The ACS is practically shouting it here:“You don’t have to hit your spot on the first try, but if you’re not going to make it, go around!” Even today, having administered many private pilot practical tests, applicants still may react with surprise when I mention they “could have gone around” after landing outside the -0/+200 foot box. This indicates to me that they are not truly familiar with the ACS, and perhaps their instructor isn’t, either.

This could explain why evaluators appear to use discretion if there are minor deviations from the tolerances stated in other tasks, but not this one. There’s no one-size-fits-all here, but evaluators do their best to adhere to the standards and guidance provided to them.

The inner workings of the ACS

Those new to aviation may not be familiar with the ACS’ predecessor, the Practical Test Standards. At time of this writing, the PTS is/was still in use for Flight Instructor practical tests. The PTS was a solid production, but over time the growing number of special emphasis areas became difficult to incorporate into the individual tasks of the practical test. Plus, the Airman Knowledge test (the “written”) wasn’t harmonized with the PTS. These issues and more led to the creation of the ACS.

Why the history lesson? Because the mature PTS reflected the FAA’s growing interest over time in applying the latest lessons learned in the areas of positive aircraft control, runway incursions, Controlled Flight into Terrain (CFIT), ADM, Risk Management and more. (Though slated for retirement, the Flight Instructor – Airplane PTS [FAA-S-8081-6D] still publishes a list of Special Emphasis Areas.)

Now, those special emphasis areas are incorporated into the tasks themselves — as knowledge, risk management, and skill elements. In other words the applicant must “know, consider and do” for each task. And risk management/ADM was built into the fabric of the ACS itself; many of the tasks require the applicant to be evaluated on situational awareness and proper task management, as well as their decision-making.

Wrapping a bow around it

Let’s be sure to understand that practical tests are practical, after all. Therefore the evaluator’s Plan of Action will revolve around safety. Particularly at the private pilot level, ADM, risk management and good common “horse sense” are at a premium. Evaluators are keen to be sure that applicants will be safe operators of their aircraft, first and foremost.

Circling back to the Taxiing task: recall that the applicant must use an airport diagram or taxi chart during taxi, if published. This is based on the data collected from researching runway incursions, which became a special emphasis area in the PTS days and now is found mentioned specifically in many tasks (including this one) in the ACS. This is a safety concern. At all levels of pilot certification, safety is the number one consideration both in terms of conducting the checkride as well as evaluating the applicant’s ability. Safety is the most valuable element in terms of evaluation: a safe airman trumps one who is capable of flying to USAF Thunderbirds standards.

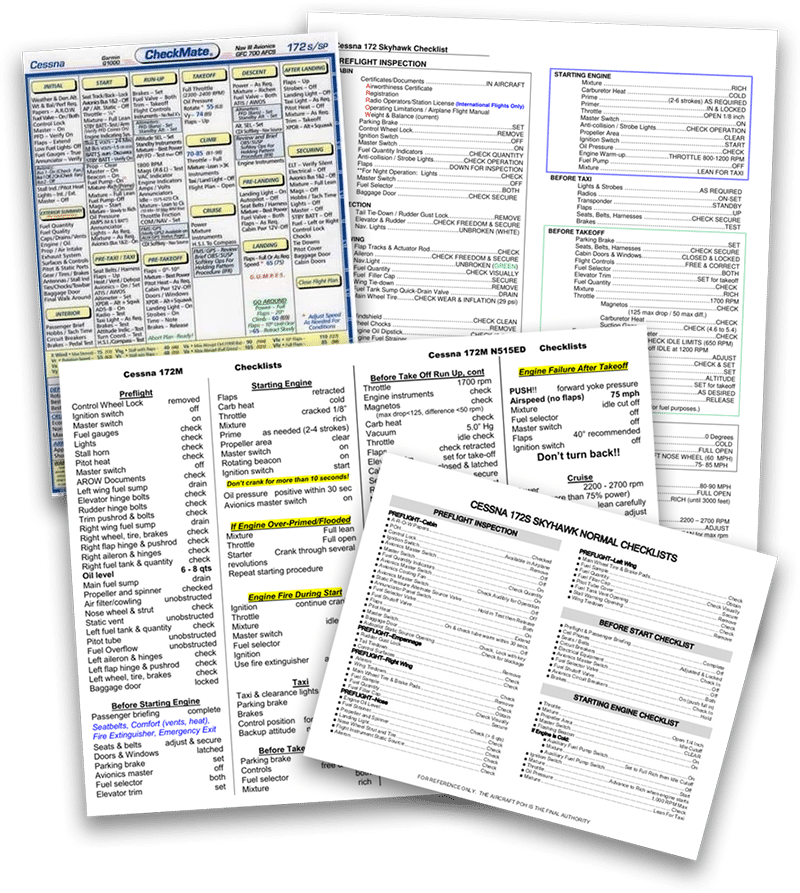

How about checklist usage? Time and time again, accidents are linked to the pilot’s procedural nature with checklists, or lack thereof. Checklists reduce errors stemming from omission and fixation, and are absolutely essential for safe operation of the aircraft. Failure to use the appropriate checklist once or twice probably won’t result in the determination of unsatisfactory performance alone, but if the airman habitually neglects to do so, the successful outcome of the practical test could be in doubt. Most evaluators are looking for systematic usage of the checklist, clearing turns between all maneuvers, and scanning technique while in the traffic pattern.

Finally, the Short-Field Approach and Landing task. At the Private Pilot level of airman certification this task is designed to evaluate not just a pilot’s flying skill, but their aeronautical decision-making. The decision to land short or long casts doubt on the pilot’s ADM in all other conceivable scenarios, and is therefore viewed very unfavorably as opposed to a Go-Around.

With this thorough approach to reading and understanding the ACS, flight instructors and student pilots alike should be “well armed” as they prepare themselves for a Private Pilot practical test.

Safe Flights!

-Ryan